In addition to their strong skills in sailing and trade, the Greek cities of western Anatolia faced an important political power to the east: the Lydian Kingdom. This powerful state controlled the inland regions and did not allow the Greek cities to expand eastward. The Lydians regarded the Ionian cities as being within their sphere of influence and often interfered in their internal affairs.

Despite this political pressure, the relationship between the Lydians and the Greek cities was not always hostile. Trade and cultural exchange flourished between the coast and the interior. Many luxury goods, including gold and fine metalwork, moved between these regions, as shown by objects such as a royal Persian figure standing on eagle heads, depicted on a late sixth-century BCE silver and gold Lydian phiale, now displayed in the Uşak Archaeological Museum From Villages to City-States.

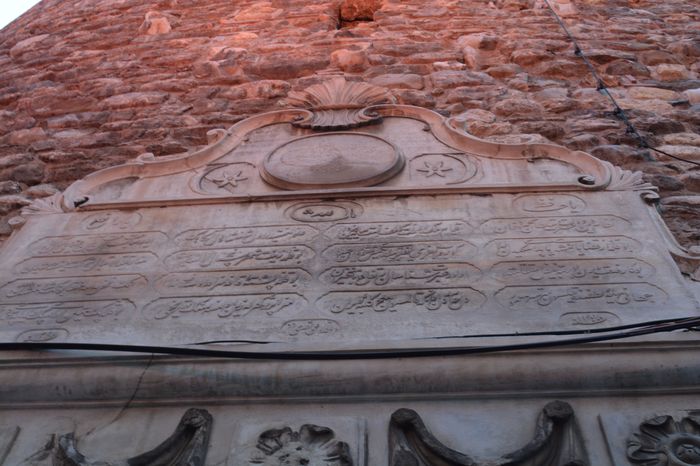

The Persian Conquest of Anatolia

In 546 BCE, the political balance in Anatolia changed dramatically when the Persian Empire invaded the peninsula. By the end of the sixth century BCE, all of Anatolia had been conquered and divided into administrative provinces known as satrapies. This marked one of the first major encounters between the Greek world and the civilizations of the East.

The Ionian cities were governed from the Persian satrapy based in Sardis, the former Lydian capital. The Persians followed a policy of tolerance toward the peoples they ruled. Local traditions, laws, and forms of government were generally respected, as long as taxes were paid and loyalty was maintained. Because of this approach, the Ionian cities retained a high degree of autonomy and continued to prosper under Persian rule.

The Royal Road and Communication Networks

One of the most important developments of this period was the improvement of long-distance communication. The Royal Road, which connected Ephesus and Sardis to the Persian capital Susa, became the main artery of the empire. The road stretched for approximately 2,300 kilometers and could be traveled in about ninety days on foot Turkey Customized Sightseeing.

Originally dating back to the Hittite period, the Royal Road was the first known highway system with regularly spaced post stations and inns, located about every twenty-five kilometers, depending on terrain. Forts protected key points, and ferries helped travelers cross major rivers. This system allowed goods to move faster and more safely than ever before.

Along this road traveled wheeled carts, camel caravans, and trains of mules and donkeys. However, not only goods moved along these routes. Ideas, religious beliefs, artistic styles, and cultural practices also spread across Anatolia. In later centuries, early Christian communities would emerge in cities located along these important trade and communication networks.

Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic Age

In 334 BCE, Alexander the Great crossed the Dardanelles (Hellespont) and entered Anatolia, beginning his campaign against the Persian Empire. Most cities of western Anatolia welcomed him as a liberator from Persian rule. The main exception was Halicarnassus, which remained loyal to Persia and resisted Alexander’s forces.

Following Alexander’s victories, western Anatolia entered the long Hellenistic period, which continued after his death. During this time, Greek culture, language, and urban life spread widely. Cities gained new energy, expanded their institutions, and continued to flourish economically and culturally.

A Bridge Between East and West

From the Lydian and Persian periods to the age of Alexander, western Anatolia remained a bridge between East and West. Its cities benefited from trade, cultural exchange, and political change, laying the foundations for the later Roman and early Christian worlds.